The Kautz Glacier up Mt Rainier

15 August 2018

It is 11am and the glacier is hot. Rocks are crashing down from across the valley. We hear the Nisqually valley rumbling thousands of feet below and we are stuck. It is terrifying not being able to find a way up: the crevasses blocking our way seem impassable. Back below us is the 60° Kautz glacier that would be suicide to try and descend at this time of day, especially with the heavy packs that we had strapped on. We have to find our way to the Wapowety bivvy and we have to do this urgently.

Our trip to the massif of Mt Rainier started a number of months ago when Carlo and Paul suggested that they fly across from the East Coast for a few day’s climbing in the Cascades. How can you come to Seattle and not tackle the monster that dominates the horizon? We certainly couldn’t. Our team quickly caught the attention of Charlie and David who wanted in. With the planning done, which included car rental, food, gear, gear, and more gear, finally we felt ready to take on some mountains. Some of the gear arrangements required technical ice tools that we would need for the two AI3 (Alpine Ice Climbing Grade 3) steps up the Kautz glacier. With bags HEAVILY weighed down with all of this gear, everyone was on their way to the Pacific Northwest. Stoke levels were HIGH!

I collected the party from the SeaTac Airport in an SUV that was way too small to fit the five of us plus our gear and we were shortly making our way South to the Rainier National Park. After some navigation errors, we pulled into the National Park around 10pm and started to search around for a campsite. We found a spot near Paradise Ranger Station but it was full. Luckily, we had a secret weapon: Carlo the Italian-Stallion. We deployed the weapon to the campsite and shortly afterwards Carlo had sweet talked a nice couple into letting us share their campsite.

Our first morning had us at the Ranger station to check-in and get some last-minute beta on the route. We signed away the mountain registers and handed over our route plans: day 1 to Camp Hazard via the Van Trump route; day 2 to take us up and over the summit to the standard Disappointment Clever route and back to the Paradise parking lot. We decided to play things safe and book a second night at Camp Hazard in case things took longer than expected: we didn’t want a search and rescue party sent out when all was under control. This was a fitting harbinger. With that done, it was time to hike onto the Nisqually glacier to practice some crevasse rescue with the team.

Paradise is a beautiful area in the Rainier National Park. I can highly recommend just walking around and enjoying the views while listening to the glaciers rumble safely at a distance. It is spectacular. Loaded with ropes, ice screws, harnesses, carabiners, prussic cord, draws, pickets and more, we lugged our gear past some bewildered tourists, descended a very dodgy little scree slope and made our way to a dirty and cracked up glacier. We did find some okay-ish ice though and with crampons on, pickets out and rope tied in, we did some of the drills that might be life saving higher on the mountain. It all went smoothly enough and by 7pm we were back in the parking lot to meet up with Vlad. Vlad, the current president of the Harvard Mountaineering Club (HMC), has a wealth of ice climbing and mountaineering experience and we were all chuffed when he decided to extend his own trip to the Cascades to join us on this climb. Vlad had spent about three weeks racking up an impressive list of conquered mountains, including: The Grand Teton (5.6 free solo’d with another HMC friend), Mt Baker and some peaks in the Boston Basin in the Northern Cascades. Rainier was left in wait for this attempt.

We found a dispersed camping spot just outside the National Park for the night. I might have mentioned this before but dispersed camping is one of my favorite things about American National Forests. Essentially, you enter a National Forest and drive around until you find a suitable spot to camp. Unfortunately, our first spot was not suitable and was covered with human excrement. Disgusting… That’s the unfortunate part of opening up resources for free: you occasionally get people who abuse the privilege. Luckily, most of the time, like-minded folks use the camping to get away from the crowds. These people correctly leave the spots cleaner than they find them.

Vlad was carrying a long few weeks in his legs and motivated a casual start the next morning. Paul is always pushing for an earlier-rather-than-later approach but this time Vlad won the popular vote; we’d have plenty of time to wake up early once we got onto the mountain. Morning swung around, Vlad had pancakes on the go and we set about preparing our gear and packing lunches for the climb. As I mentioned above, our plan was to climb the mountain in two days but we decided to pack an extra dinner and breakfast for safety.

10:45 rolled around and we had one car at the Paradise parking lot and drove one back to the Comet Falls trailhead at 4,000ft (1,219m). Packs on (probably weighing around 35lb/15kg) and we were off to tackle the famed Mt Rainier. Van Trump was not quite what the blogs had led me to believe. Sure it was pretty but I was expecting a flower mecca; this was an overstatement with one or two patches of purple and yellow hanging around. It didn’t matter as our real goal lay ahead and 10,000ft above. We slogged up this huge hill pushing toward our first campsite at 10,800ft. Holy crap! That’s about 7,000ft that we had to gain; our leisurely start was going to come back to bite us for sure!

After slogging up the ridge for about 4 hours, with a splendid lunch of salami and cheese sandwiches (something that Paul and I had perfected in Colorado a few months back,) we met our fist snow slope. Boots came out and crampons went on. We also noticed some super slow climbers up ahead who seemed to be signaling for help with a mirror. I picked up the pace to try and reach them in a minimal amount of time. This turned out to be fairly naive. They were certainly moving slowly up the slope but the repeated flashing was simply their pickets catching the afternoon sunlight and there was no cause for panic. My nerves were perhaps a little on edge. Anyway, no particular harm done. We met the 4 climbers who had decided to camp at Camp Kautz (9,200ft/2,800m). They informed us of their plan to spend a day at that altitude to acclimatize and then push for a light and fast summit with a return back down the same route. Interesting… We had been told by the ranger that we were the only team attempting Kautz that week and moreover it would be suicide to attempt the down climb of Kautz in the afternoon heat. With the glacier melting out in the afternoon, rock- and ice-fall hazards are legitimate. You’d also have to contend with softer ice conditions which means sketchy gear placement. Not ideal. Anyway, here they were about to give it a try.

Above Camp Kautz we hit our first glacier - marked by the telltale signs of giant cracks called crevasses. We roped up. Although this means you travel more slowly as a team, the aim is that if a climber happens to step on a hidden snow bridge over a crevasse and falls in, then the team can dive onto their ice-picks and hopefully arrest the fall. We’d then haul the climber out from the depths of the crevasse using the crevasse rescue that we had practiced. In the past few weeks, a number of climbers had fallen into crevasses on the more straightforward and more commonly followed Emmons route up the mountain; the risk was real. Right around this stage we were really regretting our slow start in the morning as it looked like we wouldn’t make camp before 8pm; a full 9h15 of hard hiking. When we eventually did roll into Camp Hazard, we came across two more climbers who were planning a 3am assault of the mountain, also opting for the light and fast carry up and back down the same route approach… Interesting…

Okay, let’s chat about this. Vlad was concerned about the plan to carry our gear up the technical pitches of the route that awaited us. However, we ALL didn’t like the sound of descending the Kautz glacier late in the afternoon. Moreover, we REALLY didn’t want to get trapped up above 13,100ft/4000m without our sleeping or cooking gear. Okay, it is now 10pm, let’s get up at 2am and skip breakfast to make a speedy departure. We’ll stick to the original plan to carry our heavy packs up the mountain but aim to make the Wapowety bivvy spot for a 7/8am breakfast. If all went well we’d be at the summit by 8/9am and we’d be safely on our way down the DC route before lunch. Wait a moment… Skip breakfast??? How did that sound like a good idea to us???

I was born with the genes that don’t really let me sleep when a big day lies ahead. I lay awake for the 3.5 hours of rest, listening to the terrifyingly close crash of ice and rock as it was hurled down the mountain by the ever moving glaciers. At around 1:30am a massive rumble belied what must have been a huge ice-fall. It lasted for what seemed like a full 60 seconds and it sounded like it came right from where we intended to venture in only 30 minute’s time! We all got up and got going, wide-eyed and creeped-out with that noise still rumbling in our ears.

An easy hike to the top of Camp Hazard - now dangerously close to rockfall hazard and hence why climbers are opting to sleep at the lower reaches of the camp - brought us to our first obstacle of the day: the rock step down to Kautz. Okay so there was some frayed piece of rope with three strands left hanging into the abyss. Vlad tugs on one, sees the knots and while the rest of us are thinking about a rappel, he starts a down climb. Are you serious? I am NOT climbing that with my pack weighed down by this tent and without a backup rope. Vlad hit a vertical drop-off about half way down and was forced to attach himself to one of the strands to rappel the rest of the way. The rope held. In hindsight, we had two perfectly good ropes on our backs that we should have used for the rappel. The risk is that the rope gets caught after the last climber and we wouldn’t be able pull our gear down. This would force a dangerous ascent to retrieve the gear. This risk seems to be less than that of using a unknown frayed and knotted rope that has potentially been hanging there for months if not years. Anyway, we made it safely to the bottom of the step and immediately encountered our next obstacle.

Here we are on a steep scree slop under a rock face. We are partially protected by the face from rockfall above but the rocks are small and loose on the scree slope and we are above a huge cliff leading down into the darkness of the night. A slip here would take one on the ‘long ride’ down most of the 7,000ft that we had ascended the day before. With a slip that I had in Colorado still fairly raw in my mind, I froze-up clinging to the one stable rock that I could find and refusing to go on. Paul was super understanding and dropped a quick belay for me to get up this patch. Thanks Paul :).

A few meters on, we made it to the edge of the ‘Bowling Alley’ at about 4am. It isn’t really called the Bowling Alley but a friend of Carlo’s from MITOC had done this route a few weeks back (when things were cooler and more stable) and had almost been taken out by a truck-sized piece of ice as it was funneled into the chute that lay beside the Kautz glacier. Essentially you have a sheer rock face on climber’s right that has loose rock being pushed off from the glacier above. You also have the seracs that are hanging off the side of the Kautz glacier that are waiting to break off and fall with the high temperatures. These hazards are funneled into a chute that is about 100m wide. We needed to cross this chute to get to the relative safety of the Kautz itself. Ya okay… So here is the plan: we are somewhat protected by hugging the current rock face but we need to cross over this Bowling Alley. Roping up here is a bad idea because, in the event of a rockfall, we don’t want the team to get dragged down. Moreover, statistics minds ever cranking, we have to evaluate the chance of a big rock falling and hitting just one climber in the middle of the chute: it’s a pretty low probability event. If we are all spread out with a rope connecting us then we are significantly increasing the chance of something getting hit and dragged over the edge below. Lastly, we needed to be free to react to the environment and to run one way or another in the worst case scenario. Okay fine. Crampons on now so that we don’t need to stop when we reach the ice of Kautz and we can then continue directly to the far side and away from this hazard. “Let’s keep the distance spread out so we have space to run” shouts Charlie and with that he is off. My turn. Low probability event. Low probability event. Low probability event. Scratch of crampon of rock. Crunch of crampon of ice. A few more meters…

We were there! Wow. This is about the first time that morning that I was actually feeling not in imminent danger! I looked up and was met with the glorious view of Rainier casting a shadow onto the morning rays of sunlight. Mt Adams was also just peaking out from the morning glow and it was amazing. This is why we do this! Simply magical.

We spent a bit of time regaining our nerves, roping up for the simul climb of the first Kautz step and snacking on some bars. Carlo dropped his helmet which quickly slipped, bounced and disappeared into the abyss of some crevasse down below. Whoops - that’s not a good move as we start the ice climb. Kautz itself consists of two technical ice climbing sections. Early in the season the snow covers some of the steeper ice and makes the ledges more pronounced. This results in an easier climb. We were LATE in the season. This meant the steps were uncovered and the brittle Alpine ice of the glacier was fully exposed. The two steps are connected by a steep snow slope that is fairly easily traversed, giving one a nice way to mentally break this obstacle up. Vlad fearlessly geared up to tackle the first step. The idea is that he leads up for a length of rope and then either attaches an anchor and belays the rest of the team up, or he puts some gear into the ice that the team then progressively clips into to protect from the ‘big fall’ in the event of a slip. This is harder to coordinate than the belay because if one person slips the whole team could be dislodged but it is faster than the belay and we had a lot of work ahead. So it is easy… Don’t slip.

Round about this time, the two climbers from the night before caught up with us and began climbing next to our team. I think we were all grateful for their company. It is slow and painstaking work climbing this ice. Vlad leads some ice up, and the rest of us follow slowly and carefully. The ice is brittle so that means to get purchase you hit the pick, or kick a boot, two or three times before it sticks. You also often knock chunks of ice down below (it is unavoidable) and the helmet really comes into play for those below. “Dammit Carlo, you really should have something on”. Ice seems to melt in Carlo’s vicinity though so was he really ever in any danger? I don’t know.

Hit one, hit two, stick. Test. Haul. Kick one, kick two, stick. Okay this is actually fun. We got into a rhythm and made good progress up the first step. The other two climbers got slightly ahead of us but not by much. Good work for a team of six. Step two was steeper than step one but by then we had settled into a good procedure and we were making fast progress toward the top of Kautz and toward breakfast. It was nearing 8am and we were anxious to get to the bivvy spot and to assess our situation to decide whether to sleep over or not.

Our optimism was short lived. The Kautz itself was a really fun period of good ice climbing but we didn’t realize the condition of the glacier above the Kautz. The two climbers disappeared over the lip above us and we didn’t see them again until much later. We traversed up onto this flatter section and were encountered by a mine-field of crevasses… Wow… Okay…

Carlo, Vlad and David began leading a way through this traverse. “Okay fast here, I am over a snow bridge right now”. “Slow it down, big crack ahead”. “Wooah, keep me tight there, this might go”. It was hard work: route finding and staying alert, ready to stop the fall of a climber in the event of a crevasse fall. We were nearing a patch of rock that would mark the Wapowety bivvy by about 11am - way too late to be in this glacier in this condition. But there was nothing that we could do about it. We were making progress as fast as safely possible and we had the rock band in sight. Let’s just get there…

Crap. Vlad calls back, “This way is a no go. Huge crack ahead.” We traverse to the left to try and find a bridge, a narrower section, anything hopeful. Nothing. What about if we traverse back down the crevasse to the right toward the rock band. Maybe we can find a way across there. Slow progress, more crevasses. Nothing getting us across. Vlad hops across a nasty section and we see that we are stranded on an island between two giant crevasses. “It is noon, this glacier is moving and we are stuck. We need to get off this thing ASAP”, shouts Vlad. We also realize we are famished from the lack of food and most of us are burning up in the heat. Okay, let’s find a relatively stable section away from imminent crevasse danger, eat something, de-layer some of the warm clothing, suncream up and evaluate our situation. I float the possibility of moving back toward Kautz, but we all agree that the safest option is to somehow get to that rock patch. We just need to get there. Somehow… Carlo suggests we try back up to the left of the crevasse and push further up toward the seracs on the far side of the glacier. Nobody has a better idea so we agree. He takes lead. Tired, thirsty, hungry and burning, we trudge on thorough this minefield.

Carlo shouts back “I think I can jump this thing.” From where I was on the roped team, this sounded like pure insanity. All I could see is the gaping jaws of this giant crack with no bottom. I pictured Carlo flying across the hole, ice tools in hand “Cliffhanger” style. But I was too tired to protest much. Okay, the team is ready to catch the climber in the event of a fall. It ended up being a lot less dramatic than that. The path he had found was a fairly solid, if very precarious snow bridge with a little hop to clear the crack. Still. This maneuver took balls! Carlo safely cleared this obstacle and we set pickets into the snow to further protect against falls. One by one we cleared the torment of this crevasse and with Vlad finally making the hop, we were all safely on the upward side of the crack. David took the lead and some minor sections past and we came up on one last chasm before the relative safety of the rocks. Again, this ended up looking a lot worse than it was and we found a solid bridge to take us to rocks. It was 2pm, way too late, but we had made it safely. A short scramble up some more loose scree, my favorite, and we had found a resemblance of a bivvy spot at 4000m. We were beat! Sorry, for the lack of photos of this section but I think we were all too preoccupied with the task at hand to worry about documentation. We were safe for the evening.

From our campsite, Paul and Carlo got to work on melting snow so we could begin to combat our dehydration from the day’s work. Oh yeah, did I mention that the Kautz claimed one of my water bottles? I was down to only two liters to carry. Not a crisis but not ideal. Anyway, they melted snow, Vlad and I set up tents, Charlie got some food on the go, David crashed. We were taking strain from a long day out without a breakfast or lunch. Dinner was a solid mix of mashed potatoes, tuna and noodles. We wolfed that down. At about 4:30pm we saw the other group of two slowly picking their way down through the crevasse minefield on their way down from the summit. This was a huge effort from them but we also concluded that they must have had some better beta about the route through this minefield. These climbers really seemed accomplished, they worked fast and efficiently together but I wouldn’t have wanted to be anywhere near that glacier at this time of the day. Well, we were certainly glad we had gone through the pain of dragging all this equipment so far up the mountain. We drank liters of water and quickly crashed for an early night. After our ordeal today we were expecting a big day tomorrow.

A point of much entertainment and discussion throughout the climb was that of the ‘wag bag’! Because Rainier experiences so much traffic, especially up the popular DC and Emmons routes, climbers are instructed to remove all waste from the mountain. And I mean ALL waste. At the start of the climb you take a few heavy duty bags with blue sheets inside them. When nature calls, one extracts the blue sheet and lays it out. You do your business on the blue landing pad and package the parcel inside the plastic bag. You seal the bag and place this in your pack - hoping that it won’t leak. The laughable parts came along when Paul ended up experiencing some effects of the altitude and needed the bag more times than he had planned. This led to the term “reusable wag bag” being coined. David was also a particularly interesting ‘wag bag user’ making a vociferous announcement about his intentions and then returning with a proud grin once his business was done. It was as if he was carrying the trophy from his hard work.

A luxurious 4am alarm went off and this time we certainly weren’t skipping breakfast. Most of us also had pretty bad headaches all night. This was not too surprising given the fact that we had climbed from close to sea level to 4,000m in two days and added that to the dehydration from the previous day. The result was that I didn’t really sleep again… Anyway, a few Asprin, some bland oats - it seems that Kautz had claimed our honey from Charley as well - and I was feeling okay. Let’s do this.

A little path took us past what is a more established campsite than the one that we ended up at. It was a bit sad to have missed this but in the state that we were in the night before, we really couldn’t blame ourselves for having missed it. We were shortly back onto the ice, roped up and moving again. We were almost immediately thrust back into areas of hazard that morning. Seracs above us were starting to catch the morning light and with ice warming up and melting above you, you don’t want to linger.

We picked our way through more crevasses and over a strange terrain of large snow needles that are a result of the high winds that you get at altitude. An hour later we had reached Point Success. We could catch the silhouetted outline of some climbers having ascended the DC route and who were now making their way down. We couldn’t hang around. Time to get to the summit and get off the mountain before it got too hot. As we made our final approach up the snow slope leading to the summit, a giant crack sounded below us: Rainier was just warning us that she was still the one in control. We were humbled.

A short scramble up a rock step and we were there! Crater rim below us. Views extending in all directions and some tell-tale smoke escaping from the crater to remind us that we were on a very much active volcano! It was 14,411ft (4,392m) and we were at the highest point in Washington!

Our job was far from done. We had to descend the DC route with the objective hazards and crevasse bridges that the rangers had detailed a few day’s back. Luckily, having missed lunch the day before, we had the almond butter and honey sandwiches left over and we set about eating an early lunch at 8:30am on the crater of Rainier.

DC was fairly straightforward so I’ll just touch on some of the highlights. First off, the crevasses were way bigger than the ones that we had encountered on Kautz. They were actually terrifying and it made me wonder how guides were still leading clients up this route so late in the season. The bonus of the heavy foot traffic (and guides) is that the boot pack is obvious and the route down is clearly marked. We followed the boot pack over snow bridges, under seracs and across impressive crevasses. The guides placed ladders across some of the crevasses. This is one of the advantages of using a route that set by the mountain guides. However, as independent climbers, we also have to respect that we are borrowing someone else’s equipment and we kept our roped team as our primary safety for the entire descent. Nevertheless, a big thanks to the guides for these ladders! There were a total of 10 ladders to cross and they actually became quite fun to do once you got over the initial fear of standing, in crampons, over a bottomless pit on a precarious piece of aluminum.

There was a section of the route that passed what the guides had been referring to as popcorn. These were huge blocks of ice resembling giant popcorn pieces stacked on top of one another, hanging dangerously above the route. We were on edge traversing this area and did it as fast as possible, trying not to linger. There were also multiple areas of rockfall danger. Quite honestly, these made the “Bowling Alley” look like child’s play. This route was far less technical than Kautz but I couldn’t shake the feeling that we were simply playing a game of Russian Roulette with the mountain. We passed the advanced base camp (I think it is an extension of Camp Muir) and came across one of the final rockfall areas. We had to remain roped up here as the crevasse danger was ever present but the team was trying to move swiftly. Some guides short-roping clients up DC came upon us on a little ledge and we had to wait right in the line of fire of this rockfall. Having seen a giant boulder roll down about 5 minutes earlier, we were not happy with this situation but there was only space for one team at a time. A third guided team was about to enter from the other side but we managed to express our distress and they waited in relative safety for us to cross. I would have expected these teams to show more awareness and consideration for others on the mountain but they were clearly preoccupied with their own tasks. It was quite disheartening that there was so little disregard for the safety of other teams on the mountain.

A final scree descent and a glacier crossing took us to Muir. We contemplated un-roping, again to minimize the danger of objects falling from above, but when Vlad lost a foot into a hidden pit, we were reminded of the danger of hidden crevasses. Let’s keep this up to the end. Muir marks the end of the objective hazard from the mountain. It also marks some compostable toilets and a place to drop off the famed wag-bags. Thank goodness!

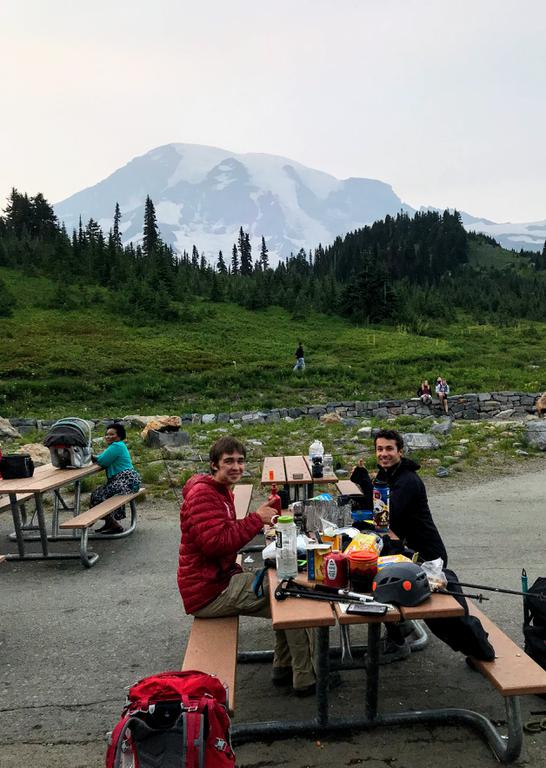

A gentle snow slop with some standing-glissading (Paul gave the seated version a valiant effort but it honestly wasn’t steep enough to achieve this) and we were off the ice. Mountaineering boots off and we were now picking our way through the tourists strolling around the walkways of Paradise Trails. With the mountain still looming behind us, we were once again in awe of its size. It was actually quite fun rolling into the parking lot with all of our gear and setting up for a meal. Other hikers start to treat you like celebrities, asking with wide eyes how it is at the top of the mountain. Energized by some food and with Rooibos tea on the go, we were happy to recount some of the reasons why they might want to stay down where they were! Nah… We were already selling the virtues of the climb, albeit recommending the climbing season be closed shortly and rather waiting until spring next year when the glaciers would once again be stable.